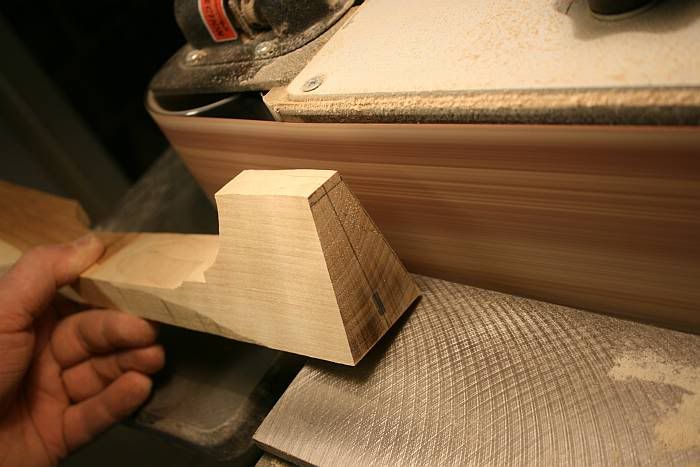

Some more neck work today. The first operation after taking the clamps off the head is to thickness the neck shaft. I do this by shimming up the nut end of the neck as much as I want the taper to be, and running it under the Safe-T planer.

The next thing is to cut the headstock outline on the band saw. On mandolins, it is common that the angle of the corner of the “ears” and front of the headstock is at a right angle to the plane of the body, not the headstock itself, as on guitars. To accomplish this, I need to hold the neck steady in the proper position while I’m cutting.

Cleaning things up with sanding drums in the drill press, the same angle must be maintained.

The traditional neck joint for these instruments is a dovetail, which is sort of tricky to do well. On the outside, the joints are indistinguishable if done well, except for the straight sides on the tapered joint; the dovetailed necks are often have an elegant concave shape on the side of the heel. Anyways, I’m too chicken for that. I’m using a straight tapered joint (as described by Siminoff in his “Bluegrass Mandolin” book), which will be glued and doweled. I believe it is at least as strong as the dovetail, there’s more gluing surface. They are no fun to take apart, though...

So, this end of the neck needs to get its final shape before it is glued in, and that is easy to do with a band saw and an edge sander.

I saw out the mortise in the body and chisel out the waste. Here’s how it looks, freshly sawn. After this, I use chisels and sanding sticks to get make the joint as nice and tight as possible.

Testing the fit... (no, the shavings are from another project!)

Finally the neck and body are glued up on a simple fixture that aligns them sideways, and it has a “cradle” that elevates the body the right distance for a proper bridge height.

Dennis, now I have that 10 CC song as an earworm

"...I don't like reggae, I love it...". Thanks a lot!

So, the neck is secured with a couple of plugs (in holes that are drilled straight down, to accommodate possible future removal), which are glued in.

With the neck joint sorted out, I can glue on the back. I should probably make a bunch of spool clamps or something, I have to use just about every clamp that I have of that general size to get a good, even clamping pressure. Crowded! Removing glue squeeze out through that oval hole is no fun, so I’m careful about using just enough glue, and I’m using tooth pick sized registering pins at both head and tail blocks so the back won’t be skidding around as attach the clamps. I’m using fish glue for this operation.

I won’t be using any binding on the back, which means I have to be extra careful not to mess up anything when I trim the overhang. I usually use a flush trimming bit, but on this one I just whittle away with a sharp chisel, to play it safe. It goes pretty fast.

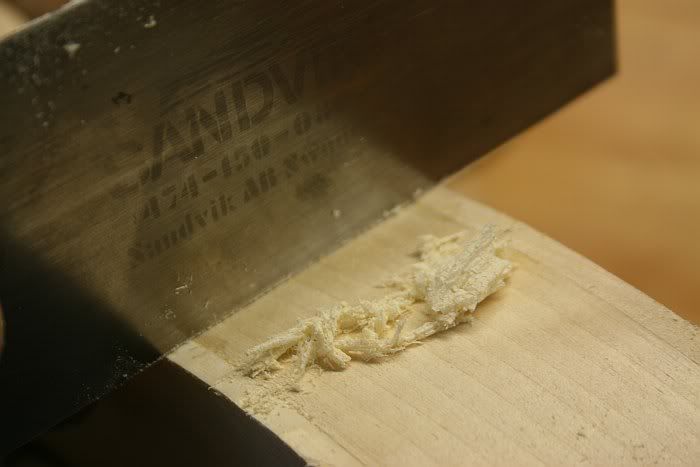

Scraping the sides with my trusty Sandvik scraper.

Here’s my setup for cutting binding rabbets on mandolins. I do this on the router table, with a shop made fixture. I used to use a the binding cutter from Stewmac, but this system allows me to use a ¼” downcut spiral bit, which cuts much cleaner. I based mine on pictures I’ve seen on one used by Lynn Dudenbostel.

Here’s a closer look. The bottom part of the jig is screwed solidly down in holes that tapped into the the steel plate that holds the router. The part with the router bit protruding from it is where the top will be resting when I cut, and this elevates the instrument off the table enough so its arched plate won’t interfere with the angle of the cut. The top part can be slid in and out for different binding widths, and is secured with the wing nut.

Action! I should probably drill out the hole for the bit some more to make dust collection more efficient... I’m doing the cutting in about 3 passes, taking only about 0.7 mm per pass, to avoid any unpleasantries.

Checking if the binding fits... As you can see, the rabbet is quite clean straight from the cutting, and there is no manual cleanup. Now, if this were an F model (or H, since this is a mandola), with scroll and points, it would be a different story.

I give the soundboard a quick wipe with shellac (to avoid lifting spruce slivers and discoloring), and install the bindings with CA glue. I like to use this packing tape to secure the bindings.

I took some pictures when I was making the fretboard. Nothing new here for most of you, but since I have now have all these pictures...

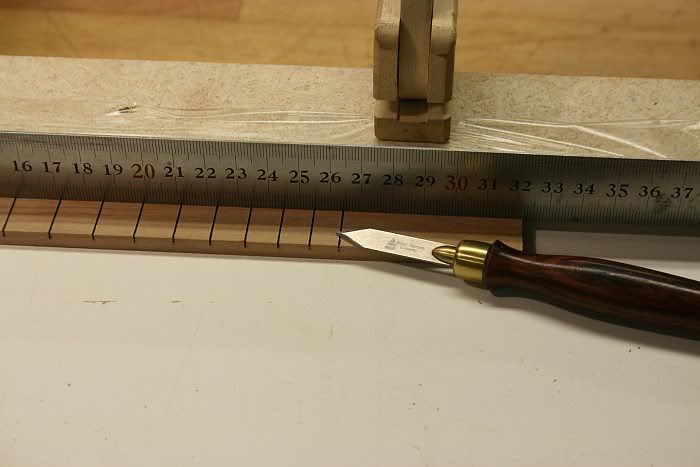

I don’t have a fretboard template for a mandola (does one exist? I haven’t checked), so I’m using my 24,9” guitar one, and using the 7th fret as my nut position. This will give me a scale of about 421.1 mm, or 16 ½” or so.

That means I can quickly cut the first 17 frets, but that is far as this template goes. There is still a bit of unslotted fretboard real estate...

...that will have to be done manually. I found an online fretboard calculator, punched in my “weird” scale length, and got the numbers for the positions of the remaining slots. Here I’m marking these on the fretboard with a marking knife.

Sawing along a square. I sure don’t miss doing whole fretboards this way!

After marking the fretboard taper from a centerline, most of the waste is cut away on the band saw. I sneak up on the line itself with a sharp plane.

I’m going to use a 12’ radius on this board, which is roughed in with the plane, and finally sanded with a straight block (jack plane body). I check my progress frequently with a straight edge, calipers on the outside edges and the fretting template.

Pressing the frets in with the drill press. I use fish glue to lube the frets, and use the depth stop to keep the pressure on the frets for minute, while I wipe off excess glue and put glue on the next fret. The idea is that this will help the fret set better as wood fibers around the barbs relax.

Missing some pictures here, but after all the frets are done, the excess is trimmed, ends filed and corners beveled, I bend the board backwards, until the board stays flat on my reference surface (jointer bed). I then use a 100 mm heavy steel profile as a caul, and hammer the frets lightly. I also check their tops thoroughly with short and long straight edges, to make sure they are all evenly set.

When everything is nice and true, I glue the board to the neck with epoxy, and pray that it will stay that way...

So, preparing things for the fingerboard. A fretboard extender is glued on (with Titebond, for convenience), and clamping is done with a screw, diagonally into the neck block. The screw will be removed before the fingerboard is attached. I also glue in other bits and pieces around the neck joint. The 12th fret cross piece is pear, everything else is birch.

My daughter checks in, and poses for a shot...

Levelling the fretboard extender with a block plane...

...until it is nice and level

Shaping those whatchamacallits with a small rasp...

...and the neck with a larger rasp...

...until it looks about right, and according to plan.

Front.

Now, I really have to start thinking about a tailpiece, that cheap stamped Gibson style one I had in mind is too small (the strap button would not be centered on the butt), besides it just doesn’t look right on this instrument. Hmmm, how about some more of that pear...? I also hate the thought of putting those “budget” Grover tuners on, so I think I will use a nice set of Gotohs that I found on the bottom of a drawer. I also found the invoice, and it seems I paid $62 for them. I didn’t put things like glue and finishing materials in my preliminary budget, so I may be getting close to the limit though. So be it.

I’m going to string this mandola up ”in the white”, so I can make the final adjustments before the finish goes on. It makes it a lot easier

not to ding up the new, soft finish when fitting bridge and nut etc. (DAMHIK)

This is my tuner dilling jig. I’ve used shop made wooden ones before, but this one just makes life easier (and the tuners work smoother). Thanks, Stewmac!

Fitting a nut before the final shaping of the neck is always a good idea. It saves the fragile edges of the neck around the nut from tear outs, plus you get a perfectly fitting nut.

Like I mentioned before, I’m planning to make a on piece pearwood bridge. I know pear has been used for bridges for other instruments in the past, I believe they are popular for lutes (?). Anyways, I’m going to give it a try, and I’ll see if I can make it work with some of that sap wood on top... BTW, pear wood smells quite disappointing when machined; not “fruity” at all!

Here’s the bridge after being fitted to the top. It is quite oversize, but it is easier to cut them down than add to them after the fact! I’m going to string it up more or less like this, let the instrument settle for a couple of days, and then cut it to its final size. This bridge is both wider and thicker than a standard Gibson type adjustable ebony mandolin bridge, but is already about 15 g, or about 1 g lighter than an adjustable bridge that I weighed (including hardware).

Headstock, with tuners and strings on. I’ll countersink and add the bushings after finishing. I think the color of the buttons matches nicely with overall color scheme of the instrument!

Back of the headstock

Varnish next!

I haven’t had much time to work on this instrument lately, but it has been sitting around “in the white” with strings on for some weeks, so it has settled in some. Everything seems to be stable, the neck is nice and straight. Its new owner came by and played it a little while ago, and we tweaked the neck profile just a hair. It sounds surprisingly nice, if I may say so!

My plan was to give it a slightly darker toner under the top coat, but I was talked into leaving it “naturally blonde”, which is appropriate for that Nordic theme, I guess... I gave the top a quick and dirty French polish before brushing it, and the rest of the instrument, with a thinned coat of Epifanes. This is how the front looked after the the second, slightly less thinned, coat.

...and the back. That varnish sure pops the grain nicely, unfortunately it also highlights boo-boo’s equally well!

The varnish seems to harden just fine. I am used to working with lacquer, so the application takes some getting used to, though. One thing I really like about this material is how easy it is to sand. I managed to get it fairly level after about 4 or 5 coats, wet sanding with 1000 grit. I then decided to rub on some tru oil, and it seems to smooth everything out nicely. This is after the second, and hopefully final, coat of tru oil.

BTW, I'm also rubbing on some tru oil on the finger board. It got grungy real fast when I was playing it in the white, so I'm hoping this will keep it a little nicer looking, for a while anways...

The back

…and we’re done! Just in time too, but hey, story of my life and all that.

Front

Back

Front

Back

Side

Headstock, front

Headstock, back

The maker, taking her for a spin.

The final budget

Spruce: Free

Pearwood: Free

Plywood: Free

Birch : $3

Tuners: $62

Fret wire: $2

Carbon fibre truss rod: $5

Side position markers, end pin, wood plugs, nut: $5

Finish , glue etc $10

Tail piece: $10

Total: $97

Thanks for looking!